Being Creative in Goma

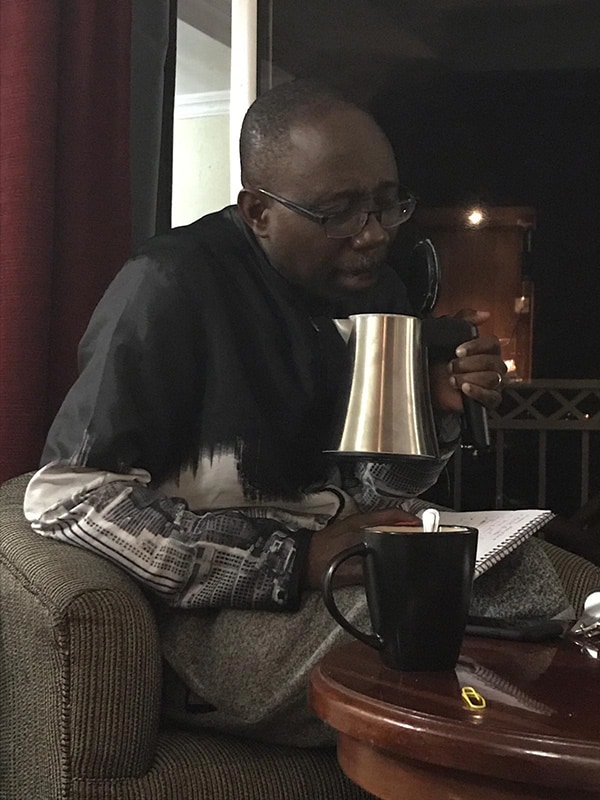

Norbert Soke gets creative by using a teapot to create an echo so that he could hear during the phone calls.

Here’s something you don’t see every day: A man talking into a coffee pot.

But for CDC epidemiologist Norbert Soke and a team of colleagues in a hotel in Kinshasa, it was a way to break through a technological communication barrier. The pot held not coffee, but a cell phone—and speaking into it created an echo chamber that let the team power through a poor connection with colleagues in Goma.

“That’s the beauty of field work. You need to be creative sometimes,” Soke says.

Soke grew up in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and earned a medical degree at the University of Kinshasa in 1995. After living and working the United States for almost two decades, he returned to DRC in March as CDC and other global health agencies battled the current outbreak of Ebola virus disease in the eastern part of the country.

Not only is he a Congolese native, but he worked in the affected area as a health project manager for the relief agency World Vision in the late 1990s.

“This is really close to the heart for me,” Soke says. He’s very appreciative of the colleagues who have volunteered to help in his home country despite their busy professional lives “because they see the importance of the work being done down there.”

Norbert Soke leads a meeting in Goma.

Dr. Soke has been passionate about public health since the beginning of his medical career. He came to the United States in 2000, earned a master’s and PhD in epidemiology at the University of Colorado Denver, and joined the CDC as an Epidemic Intelligence Service officer in 2015 to gain more training in applied epidemiology to improve the health of communities.

During the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, he worked in Guinea to help quell the worst Ebola epidemic to date. But the current outbreak is more challenging, since it takes place in a zone with armed conflict.

“We know what to do when there is an Ebola outbreak. This is the 10th outbreak in the Congo,” he says. “However, this time is different. We are in an uncharted territory.”

Dozens of armed groups are still battling government troops and each other in Congo’s northeast after a quarter-century of conflict. Several health workers have been killed, and the lack of security has kept CDC staff from getting the type of direct access to the field as they had in the West African outbreak, Soke says.

Because of his past experience and his knowledge of the country, he was dispatched to Goma to coordinate the CDC’s efforts on infection control, epidemic surveillance, vaccinations, and border health. Workdays regularly lasted more than 12 hours, filled with reports and meetings with the Congolese government’s Ebola response leadership and various partner agencies—and efforts to penetrate the cloud of fear and misinformation that have left some of the most vulnerable populations suspicious and hostile toward health workers.

“There was also some level of misinformation and community resistance in West Africa, but not to the level that we are experiencing in this current outbreak,” he says.

The battle against Ebola could benefit from more outreach by trusted local voices who can convince people to report illnesses or deaths and be vaccinated when they may have been exposed, Soke says. Despite the challenges, he says that CDC and its volunteers have made a positive difference, and most locals and other partners appreciate their contributions.

“We have to consider the fight against Ebola in the current outbreak as a marathon,” he says. “It’s going to take a while. We may only see incremental changes at time and we need to be prepared for a long run but I am convinced that the outbreak will be kept under control in the future.”