Pregnant Women and Flu Vaccination, Internet Panel Survey, United States, November 2017

Key Findings

- As of early November 2017, influenza (flu) vaccination coverage among pregnant women before and during pregnancy was 35.6%.

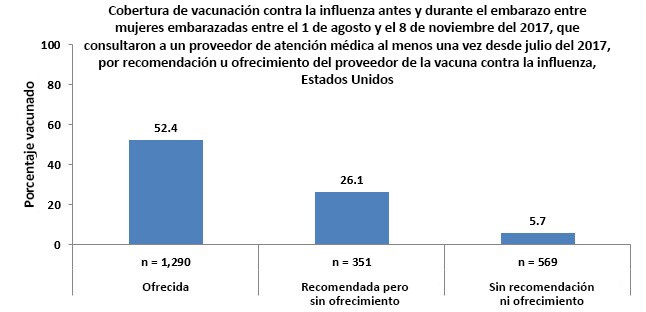

- Most pregnant women (97.9%) reported visiting a doctor or other medical professional at least once before or during pregnancy since July 1, 2017. Among these women, 58.7% reported receiving a recommendation for and offer of flu vaccination from a doctor or other medical professional, 15.6% received only a recommendation for and no offer of flu vaccination, and 25.7% did not receive a recommendation for or an offer of flu vaccination.

- Vaccination coverage among these women was 52.4%, 26.1%, and 5.7%, respectively.

- A change in survey methodology in November 2017 allowed more women to participate in the survey using a smartphone or other handheld device (73.4% compared with 16.5% in November 2016).

- This shifted the characteristics of the survey sample, so comparisons of vaccination coverage from November 2017 to previous survey years cannot be made.

Conclusion/Recommendation

- Almost two thirds of pregnant women have not been vaccinated against flu as of early November 2017.

- Health care providers are encouraged to continue to strongly recommend and offer flu shots to pregnant women throughout the flu season to protect mothers and their infants.

Pregnant women are at increased risk for complications due to flu, particularly during the second and third trimesters. Additionally, infants younger than 6 months also are at high risk of serious flu illness but are too young to be vaccinated (1,2). Vaccination lowers the risk of flu illness in pregnant women and flu-related hospitalizations in their infants for the first several months of life (1,3-9). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Nurse Midwives, and the American Academy of Family Physicians recommend flu shots for all women who are or will be pregnant during the flu season (1,3-5).

To estimate flu vaccination coverage by early November 2017, CDC analyzed data on flu vaccination from an Internet panel survey conducted November 1–8, 2017, among women who were pregnant any time since August 1, 2017. The results of this survey provide information for use in vaccination campaigns during National Influenza Vaccination Week (December 3–9, 2017). This report provides early estimates of vaccine uptake since July 2017 by pregnant women. In the previous two flu seasons, vaccination coverage increased by approximately 7–10 percentage points from the early season to the end of the season. Final 2017–18 flu season vaccination coverage estimates for pregnant women will be published in September 2018.

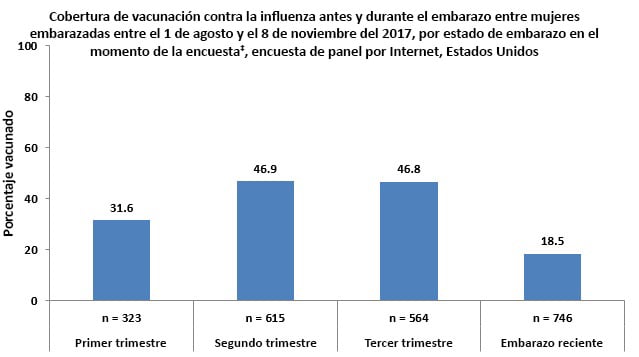

Coverage by Pregnancy Status

- Vaccination coverage was lower among pregnant women who reported being recently pregnant (women with a pregnancy that ended between August 1, 2017 and the time of the survey) (18.5%) and women who reported being in their first trimester (31.6%) at the time of the survey compared with pregnant women who reported being in their second (46.9%) or third (46.8%) trimesters at the time of the survey.

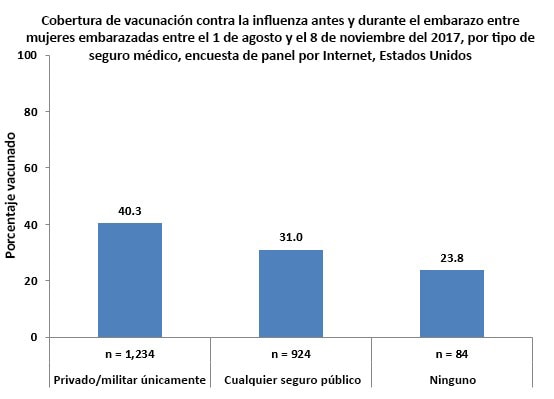

Coverage by Type of Medical Insurance

- Pregnant women who reported having only private/military insurance during pregnancy had higher vaccination coverage (40.3%) than pregnant women who reported having any type of public medical insurance (31.0%) and those who reported not having insurance (23.8%).

- Approximately 1 in 25 (4.1%) pregnant women reported not having medical insurance.

Coverage by Health Care Provider Recommendation and Offer

- Most pregnant women (97.9%) reported visiting a doctor or other medical professional at least once before or during pregnancy since July 1, 2017. Among these women, 58.7% reported receiving a recommendation for and offer of flu vaccination from a doctor or other medical professional, 15.6% received a recommendation but were not offered the vaccine, and 25.7% did not receive a recommendation for or offer of flu vaccination.

- Flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women was highest (52.4%) among women who reported their doctor or other medical professional recommended and offered the vaccination.

- Among pregnant women who reported they received a recommendation for but no offer of vaccination from their doctor or other medical professional, 26.1% were vaccinated.

- Only 5.7% of pregnant women were vaccinated among those who reported they did not receive a recommendation for or offer of vaccination from their doctor or other medical professional.

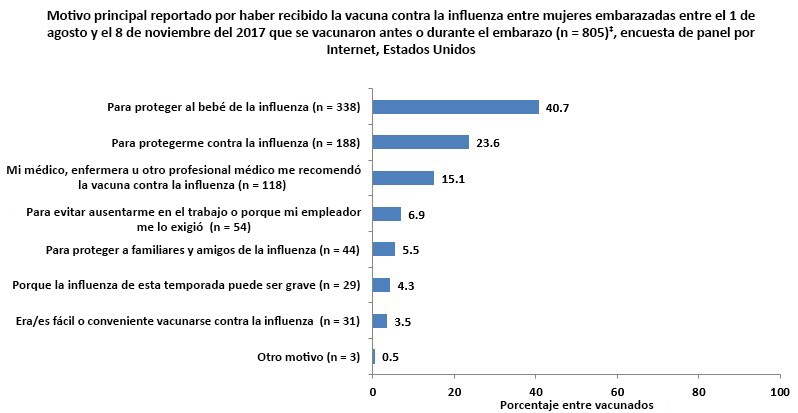

Main Reason for Receiving Vaccination

Respondents who had been vaccinated by the time of the survey‡ were asked to report their main reason for receiving a flu vaccination.

- The most commonly reported reason for receiving a flu vaccination was “to protect my baby from flu” (40.7%).

- The second most commonly reported reason was “to protect myself from flu” (23.6%), and the third most commonly reported reason was that their health care provider recommended flu vaccination to them (15.1%).

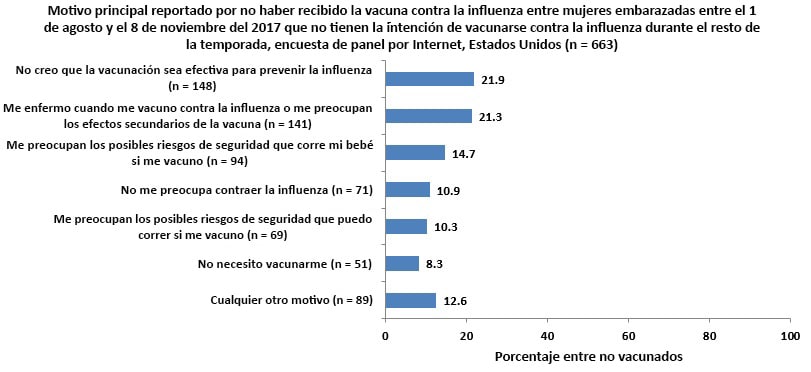

Main Reason for Not Receiving Vaccination

Unvaccinated respondents who reported that they did not intend to be vaccinated during this flu season§ were asked their reasons for not receiving or not planning to get a flu vaccination.

- The most commonly reported reason for not receiving vaccination was “I do not think the flu vaccine is effective in preventing the flu” (21.9%).

- The second most commonly reported reason for not receiving vaccination was concern about getting sick from flu vaccination or worry about side effects of the vaccination (21.3%).

- Two other reasons commonly reported by respondents were “concern about possible safety risks to my baby” (14.7%) and not being concerned about getting the flu (10.9%).

- Barriers to vaccination access, such as lack of medical insurance or cost of the vaccine, lack of time, unavailability of the vaccine, and lack of knowledge regarding where to get the vaccine were rarely reported as a main reason for not receiving a flu vaccination.

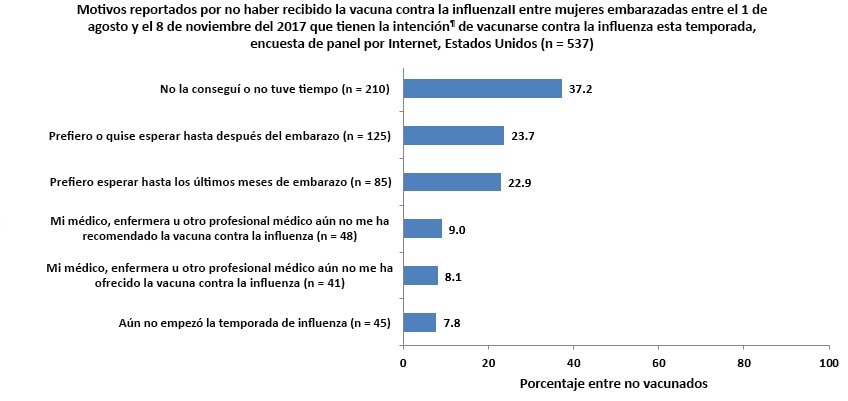

Reasons for Not Yet Receiving Vaccination

Unvaccinated respondents who reported that they intended to be vaccinated during this flu season¶ were asked their reasons for not yet receiving vaccination.

- The most commonly reported reason for not yet receiving a flu vaccination was not having gotten around to it or not having the time (37.2%).

- The next two most commonly reported reasons for not yet receiving flu vaccination was that they prefer to wait until after their pregnancy (23.7%) or prefer to wait until later in their pregnancy (22.9%).

Characteristics of Survey Respondents

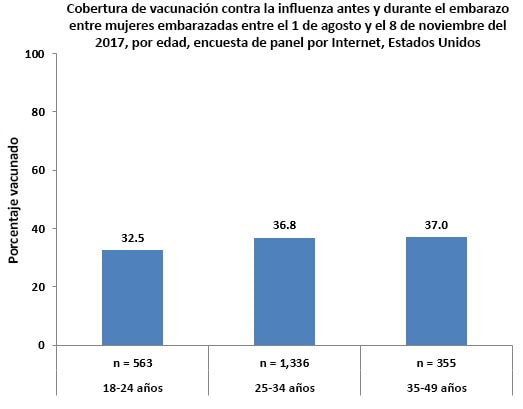

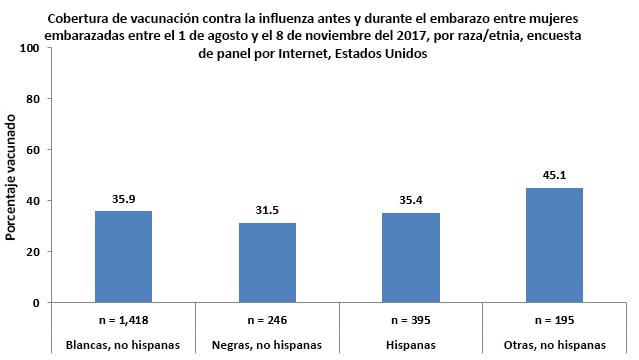

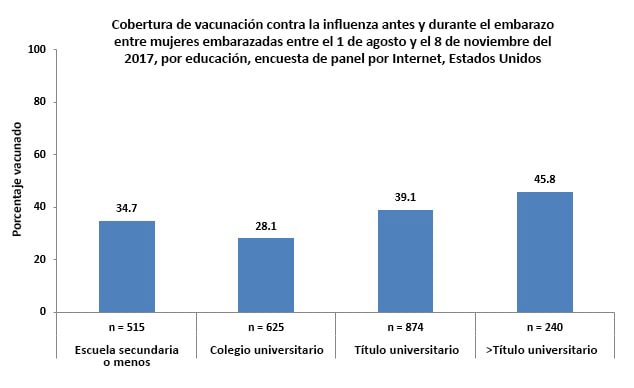

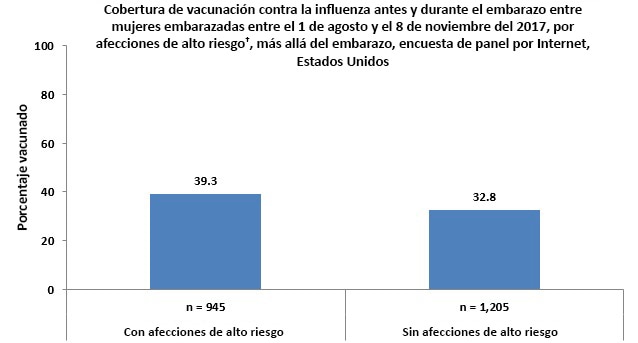

- A total of 2,254 women pregnant anytime from August 1–November 8, 2017, were included in the survey. More information by demographic subgroups can be found in the Demographic Table [XLS – 14 KB].

- A higher proportion of women using a smartphone or other handheld device were included in the sample in November 2017 (73.4%) compared with November 2016 (16.5%).

- Vaccination coverage among women who completed the survey on a handheld device was 32.3%, compared with 43.1% among women who completed the survey on a desktop or laptop computer and 53.0% among women who completed the survey on a tablet.

- There were also increased numbers of pregnant women participating in the November 2017 survey who were younger, have less than a college degree, have public insurance, and who reported being recently, but not currently, pregnant at the time of the survey compared with November 2016.

What Can Be Done?

Overall, early 2017–18 season flu vaccination coverage before or during pregnancy among women pregnant any time from August 2017 through the time of the survey was 35.6%, suggesting that nearly two-thirds of pregnant women are not protected against influenza. Pregnant women may receive any licensed, recommended, age-appropriate influenza vaccine at any time during pregnancy, before and during the influenza season, as soon as vaccine is available. A strong provider recommendation with an offer of vaccination may help improve vaccination coverage, especially for pregnant women who were not vaccinated but intended to get vaccinated, including the 37% who had not had the opportunity or time and the 17% who reported not receiving a recommendation or offer of vaccination. CDC [280 KB, 2 pages], ACOG, and the American College of Nurse-Midwives provide resources to help providers recommend and offer vaccination or refer for vaccination. If a provider cannot offer vaccination in their office, a referral to the nearest site where a vaccination can be given can help a pregnant woman receive the necessary vaccines to protect themselves and their infant.

In September 2017, results of a study conducted during the 2010–11 and 2011–12 influenza seasons were published which reported an association of repeated flu vaccination during the first trimester with spontaneous abortion (10). Multiple earlier studies have indicated there is no association between flu vaccination and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including spontaneous abortion (11-15). Many pregnant women who had not been vaccinated but intended to get vaccinated this season reported preferring to wait until later in their pregnancy or after pregnancy. Since flu poses a danger to pregnant women and their infants, CDC, ACIP, and ACOG continue to recommend flu vaccination for pregnant women during any trimester to protect both pregnant women and their babies from flu infection (16-17). CDC and ACOG have posted information to help providers answer questions that may come up after their flu vaccination recommendation.

To improve flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women:

Medical professionals are reminded to implement the National Vaccine Advisory Committee’s Standards for Adult Immunization Practice (18):

- Assess the vaccination status of pregnant women at each visit.

- Standing orders and provider reminders can be used to ensure patient vaccination status is assessed at every visit (19).

- Strongly recommend flu vaccination and provide information about:

- The risk of flu and related complications for pregnant women and their infants, including severe illness in pregnant women and flu-related illness and hospitalization in their infants;

- The benefits and risks of flu vaccination for mothers and their infants;

- The protection transferred to infants by vaccination during pregnancy, since infants younger than 6 months old cannot be vaccinated themselves;

- The well-established safety record of flu vaccine for pregnant women and their babies.

- Offer flu vaccination or refer women to another provider who can give the flu vaccine.

- Ensure that receipt of vaccination is documented in the patient medical record and immunization registry.

Medical professionals should vaccinate pregnant women and others throughout the flu season:

- Peak flu activity in the United States most often occurs from December through February, however, activity can last as late as May.

- Providers should strongly recommend their unvaccinated patients, including pregnant women and the contacts and caregivers of pregnant women and their infants, to receive a flu vaccination as soon as possible and before flu activity increases in their community.

- Providers should continue to offer flu shots to unvaccinated pregnant women for the duration of the flu season, even if flu activity has decreased in their community, since more than one type or subtype of flu may cause illness in a single flu season.

Information is available at:

- American College of Nurse-Midwives. Immunization Resources for Providers.

- CDC. Pregnant Women and Influenza (Flu).

- CDC. Pregnant? You Need a Flu Shot! Information for Pregnant Women. [780 KB, 2 pages]

- CDC. Letter to Health Care Providers of Pregnant Women – 2017-2018 Flu Season [497 KB, 2 pages].

- CDC: Making a strong vaccine referral to pregnant women [280 KB, 2 pages]

- Health Map Vaccine Finder.

- Text4baby. Texts to keep you and baby healthy.

Data Source and Methods

CDC conducted an Internet panel survey from November 1–8, 2017 to provide early-season estimates of flu vaccination coverage and information on knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to flu vaccination among pregnant women. Women 18–49 years who were pregnant at any time since August 1, 2017, were recruited from SurveySpot, a general-population Internet panel. Eligible respondents were either pregnant at the time of the survey or had a pregnancy that ended between August 1, 2017 and the time of the survey. Of 2,333 panel members who were eligible and started the survey, 2,255 (96.7%) completed the online survey. One respondent was excluded from the analysis due to missing information about receipt of flu vaccination. Data were weighted to reflect the age, race/ethnicity, and geographic distribution of the total U.S. population of pregnant women (20-22). SurveySpot is the same recruitment mechanism that was used in the November 2016 survey; however, a change in survey methodology shifted the proportion of survey respondents using a smartphone or other handheld device to participate in the survey from less than 20% in 2016 to 73% in 2017. This change in survey methodology may explain the shifting of the sample to pregnant women of younger age, less education, and with public insurance compared with the last year’s survey. Prior research has found that Americans who rely on smartphones for online access are more likely to be younger, have lower household income and lower levels of education, and be non-white compared with those who have other options, such as a desktop or laptop computer, for Internet access (23). These characteristics have also been found to be associated with lower vaccination coverage in pregnant women (24).

Survey respondents were asked if they had received a flu vaccination since July 1, 2017, and if so, in which month they received it, as well as whether they received the vaccination before, during, or after pregnancy. Pregnancy status questions included whether respondents were currently pregnant at the interview time or had been pregnant any time since August 1, 2017. Women who reported being vaccinated since July 1, 2017, and who were vaccinated before or during pregnancy were counted as vaccinated. All respondents were asked if their doctor or other medical professional had recommended or offered the flu vaccine. They were also asked about their attitudes toward and beliefs about flu and flu vaccination.

Weighted analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.3) survey procedures. Because the opt-in Internet panel sample was based on those who initially self-selected for participation in the panel rather than a random probability sample, statistical measures such as calculation of confidence intervals and tests of difference were not performed (25). A difference of 5 percentage points was considered a notable difference.

Limitations

These results are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution. The follow-up Internet panel survey in April 2018 will assess flu vaccination coverage at the end of the flu season.

The findings in the report are subject to several limitations.

- The sampling methodology changed from November 2016 to November 2017, including more pregnant women using smartphones and other handheld devices besides tablets to respond to the survey in the sample. This change limits the ability to make comparisons to estimates in prior years.

- The sample was not necessarily representative of all pregnant women in the United States, because the survey was conducted among a smaller group of volunteers who were already enrolled in SurveySpot rather than a randomly selected sample.

- Some bias might remain after weighting adjustments, given the exclusion of women with no Internet access and the self-selection processes for entry into the panel and participation in the survey. Estimates might be biased if the selection processes for entry into the Internet panel and a woman’s decision to participate in this particular survey were related to receipt of vaccination.

- All vaccination results are based on self-report and not validated by medical record review. Estimates from Internet panel surveys may not be directly comparable to estimates from population-based surveys because of the difference in sampling between the surveys.

Despite these limitations, Internet panel surveys are a useful surveillance tool for timely early season and post season evaluation of flu vaccination coverage and knowledge, attitude, practice, and barrier data.

AUTHORS: Helen Ding, MD, MSPH1; Carla L. Black, PhD2; Sarah W. Ball, ScD3; Rebecca V. Fink, MPH3; Amy Parker Fiebelkorn, MSN, MPH2; Katherine E. Kahn MPH4 ; Peng-Jun Lu, MD, PhD2; Walter W. Williams, MD, MPH2; Denise D’Angelo, MPH5, Lisa A. Grohskopf6; Stacie M Greby, DVM,MPH2

1CFD Research Corporation, Huntsville, AL; 2Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; 3Abt Associates Inc., Cambridge, MA; 4Leidos, Atlanta, GA; 5Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 6Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC

Related Links

- Pregnant? Get a Flu Shot!

- Standards for Adults Immunization Practice

- Influenza vaccination coverage: FluVaxView

- 2016-17 end-of-season MMWR

- 2016-17 early season MMWR

- 2015-16 end-of-season online report

- 2015-16 early season online report

- 2014-15 end-of-season MMWR

- 2014-15 early season online report

- 2013-14 end-of-season MMWR

- 2013-14 early season online report

- 2012-13 end-of-season MMWR

- 2012-13 early season online report

- 2011-12 end-of-season MMWR

- 2011-12 early season online report

- 2010-11 end-of-season MMWR

- 2010-11 early season online report [427 KB, 6 pages]

- Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System website

- Prevention and Control of Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States, 2016–17 influenza Season

- Text4Baby

- SSI

- SurveySpot

- Follow CDC Flu on Twitter: @CDCFlu

References/Resources

-

- Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–United States, 2016-17 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-05):1–54.

- Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, et al. The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. N Engl J Med 2006;355:31-40.

- Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2017;66(No. RR-02):1–20.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 608 Obstet Gynecol 2014; 124:648–51. Joint statement for pregnant women about Influenza.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Immunization for women. Accessed November 28, 2016.

- Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE, et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med 2006;355:31-40.

- Poehling KA, Szilagyi PG, Staat MA, et al. Impact of maternal immunization on influenza hospitalizations in infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204(6 Suppl 1):S141–8.

- Madhi SA, Nunes MC, Cutland CL. Influenza vaccination of pregnant women and protection of their infants. N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 11;371(24):2340.

- Tapia MD, Sow SO, Tamboura B et al. Maternal immunisation with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine for prevention of influenza in infants in Mali: a prospective, active-controlled, observer-blind, randomised phase 4 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep;16(9):1026-35.

- Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP et al. Association of spontaneous abortion with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine containing H1N1pdm09 in 2010–11 and 2011–12. Vaccine 35 (2017) 5314–5322

- Moro PL, Broder K, Zheteyeva Y, et al. Adverse events in pregnant women following administration of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and live attenuated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 1990-2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:146.e1-7.

- Irving SA1, Kieke BA, Donahue JG et al. Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and spontaneous abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jan;121(1):159-65.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H et al. Inactivated Influenza Vaccine during Pregnancy and Risks for Adverse Obstetric Events. Obstetrics & Gynecology: September 2013 – Volume 122 – Issue 3 – p 659–667

- Nordin JD, Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G et al. Maternal Influenza Vaccine and Risks for Preterm or Small for Gestational Age Birth. The Journal of Pediatrics. Volume 164, Issue 5, May 2014, Pages 1051-1057.e2

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Romitti PA et al. First Trimester Influenza Vaccination and Risks for Major Structural Birth Defects in Offspring. J Pediatr. 2017 Aug;187:234-239.e4.

- ACOG. It is Safe to Receive Flu Shot during Pregnancy. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2017/It-is-Safe-to-Receive-Flu-Shot-During-Pregnancy

- CDC. Flu Vaccination & Possible Safety Signal. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccination-possible-safety-signal.html.

- National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: Standards for Adult Immunization Practice. Public Health Rep 2014;129:115-23.

- The Guide to Community Preventive Services: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination. Accessed November 14, 2017.

- Guttmacher Institute. Total pregnancies by occurrence includes total births, abortions by occurrence and miscarriages Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/datacenter.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: Final data for 2015. National vital statistics report; vol 66, no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr66/nvsr66_01.pdf.

- Curtin SC, Abma JC, & Kost K. 2010 pregnancy rates among U.S. women (supplemental table). NCHS Health E-Stat. 2015. Accessed November 28, 2016.

- Pew Research Center. U.S. smartphone use in 2015. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015/. Accessed November 30, 2017.

- Ding H, Black CL, Ball S, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, 2016–17 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep 2017;66:1016-22.

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Report of the AAPOR Task Force on non-probability sampling. Accessed November 14, 2017.

Footnotes

*Excludes 6 currently pregnant women with unknown trimester of pregnancy.

†Currently have conditions other than pregnancy associated with increased risk for serious medical complications from influenza, including chronic asthma, a lung condition other than asthma, a heart condition, non-gestational diabetes, a kidney condition, a liver condition, a weakened immune system caused by a chronic illness or by medicines taken for a chronic illness, or obesity.

‡Excludes 249 women who reported being vaccinated after their pregnancy ended.

§Includes unvaccinated respondents who reported that they probably or definitely do not intend to be vaccinated before the end of the flu season.

||Respondents could select more than one reason.

¶Includes unvaccinated respondents who reported that they probably or definitely will get vaccinated before the end of the flu season.